If you can’t cross-check the transactions in your business or organisation with an automated solution, you are leaving opportunity for corruption and fraud.

In the recent ICAC NSW public enquiry the only thing the corrupt offenders were worried about was someone “sniffing around”…

‘In a text message read to the inquiry, a Downer employee urged one of the transport bureaucrats to speed up work related to one contract “so people don’t start sniffing around and asking questions”.’

Time after time businesses rely on ad hoc annual audits by big accounting firms, only examining data samples. More often than not, when they do find anything, the money is long gone, the list of corrections required resembles a phone book and it costs more than it’s worth to try to claw back overpaid invoices, or worse – your business or organisation ends up an embarrassing headline.

“A Sydney council employee netted tens of thousands of dollars in kickbacks after awarding contracts valued at $4.3 million, a corruption inquiry has heard.”

Corruption is generally defined as the misuse of public power for private gain. The most identified forms, according to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), are bribery, embezzlement, money laundering, concealment, and obstruction of justice. More specifically, these broad terms can include seeking and accepting secret commissions by public officials, fraud, undeclared conflicts of interest, election tampering, and nepotism.

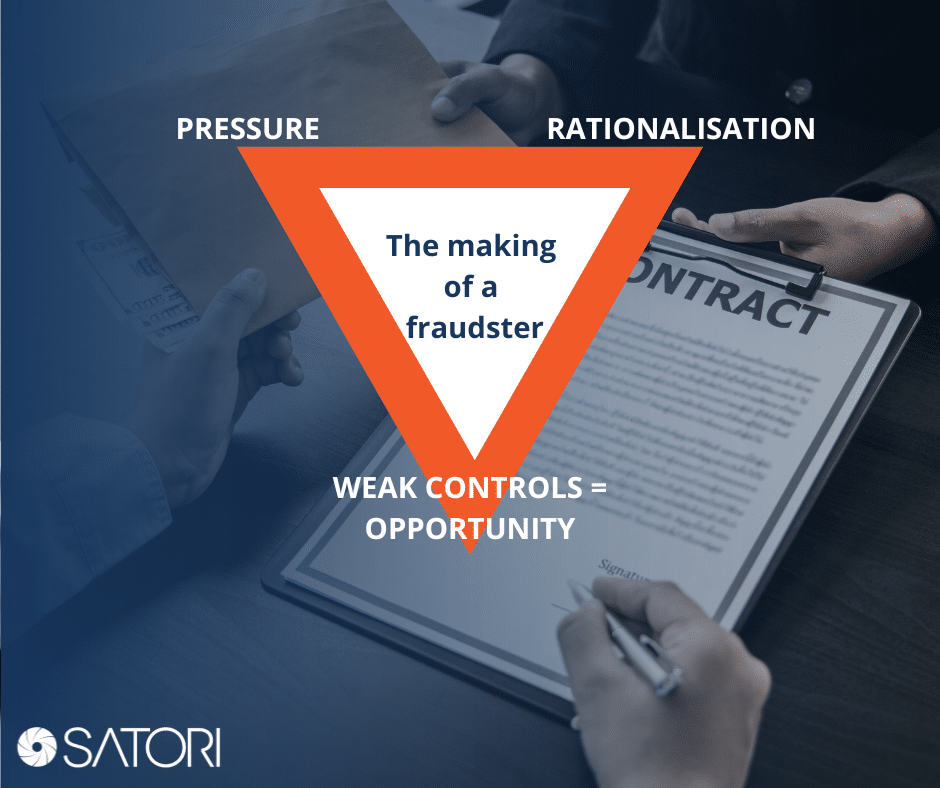

The fraud triangle is the basic model used to describe the three essential factors that must be present for fraud to occur: opportunity, rationalisation, and pressure. In simpler terms, the model suggests that someone must have the chance to commit fraud, a motive to justify it, and a need for it to occur.

The fraud triangle is the basic model used to describe the three essential factors that must be present for fraud to occur: opportunity, rationalisation, and pressure. In simpler terms, the model suggests that someone must have the chance to commit fraud, a motive to justify it, and a need for it to occur.

Opportunity refers to the circumstances that make it possible for someone to commit fraud without getting caught.

For example, weak internal controls, a lack of oversight, or access to sensitive financial information can create an opportunity for fraudsters.

Rationalisation is when the fraudster convinces themselves that committing fraud is justified or necessary. Rationalisation can take many forms, including blaming others for their financial troubles, believing they are underpaid, or convincing themselves that the company owes them. (what is the fraud triangle?)

Pressure refers to the motivation or need for someone to commit fraud. Financial pressures, such as debt or gambling addiction, are common examples of pressure that can drive individuals to commit fraud.

The solution is simple

- To prevent fraud, businesses must identify and mitigate the opportunities, rationalisations, and pressures that could lead to fraudulent behaviour.

- Implementing strong internal controls, providing employees with appropriate training, and regularly reviewing financial statements can help prevent fraud from occurring.

- It’s also important to be aware of the warning signs of fraud, such as unusual transactions, unexplained discrepancies, and changes in behaviour.

- By staying vigilant and taking proactive steps to prevent fraud, businesses can protect themselves from the potentially devastating effects of fraudulent activities.

Learn more about the power of the Satori Solution to bulletproof your internal controls.